EPISODE:57

By THAN HTUN (GEOSCIENCE MYANMAR)

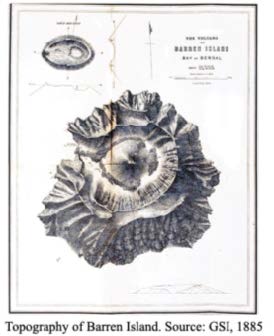

Historical Expeditions to Barren Island

This article continues from Episode 56, highlighting key points from FR Mallet’s 1895 account of historical expeditions to Barren Island since 1595.

Blair, 1789.: I have made unsuccessful attempts, at the libraries mentioned, to discover the original of Captain Blair’s report on the Andamans, part of which, relating to Barren Island, is quoted by Lieutenant Colebrooke in the Asiatic Researches. The following letter, however, dated 19 April 1789, serves to supplement the above: “To the Right Hon’ble Charles Earl Cornwallis, KG, Governor-General, etc., in Council: -

My Lord * * * After examining Diligent Strait and the archipelago, I proceeded to Barren Island and found the volcano in a violent state of eruption, throwing out showers of red-hot stones and immense volumes of smoke. There were two or three eruptions while I was close to the foot of the cone; several of the stones rolled down and bounded a good way past the foot of it. After a diligent search, I could find nothing of Sulphur or anything that answered the description of lava. * * * I have, &c. “Archibald Blair”.

The proceeding account is, in most respects, very similar to that in the report alluded to, and the chief interest lies in the final sentence. I have argued, on other grounds, that the lava streams that now extend from the central cone westward towards the sea were emitted after Blair’s visit, but his statement that after diligent search, he could find nothing resembling lava, put the question beyond discussion. It is scarcely conceivable that anyone, however inexperienced in volcanic geology, could fail to recognize the true character of such typical streams at first glance. There is, however, still further proof that the lava was emitted after Blair’s time. From the points of issue, the streams flowed down the slope of the cone, and their heads now constitute a portion of its surface so that there have been no accretions to the cone since the occurrence in question. However, it is shown in the succeeding paragraphs that the cone has greatly increased in bulk since 1789, and any lava emitted then, or previously, and solidified on its flanks, would now be deeply buried beneath the later products of eruption. I have previously stated that no fragmentary ejecta has even fallen directly from the crater onto the surface of the lava, which must, therefore, have been emitted after the last eruption of such material. In other words, the lava must be the latest volcanic product and cannot have been emitted earlier than 1804, the date of the last outburst of which we have any record. We have no reason to suppose that the different streams were emitted at considerable intervals, and the existence of the hot spring in 1832 shows that the southern stream, at least, had been poured forth before that date.

Captain Blair’s landing on the island remains the first, of which we have any record.

It is worthy of mention in connection with Blair’s visit that Test’s “view of the volcano on Barren Island, bearing east, about one mile off,” taken the day before Blair landed, gives the means of arriving at an approximation to the height of the newer cone at that time. The sketch represents the summit of the cone as rising very slightly above the skyline of the old crater rim behind it, and a careful comparison of corresponding points in the sketch and in Hobday’s map of 1884 shows that the artist, the summit of the cone, and the eminence on the old crater rim which Hobday marked as 1,060 feet, in height, were in a line; and likewise shows that the eminence in question was concealed, and only just concealed, by the summit of the cone: in other words, the eminence and the cone subtended almost the same angle, their respective distances from the point of view, and the height of the eminence, being obtained from the map, give the height of the cone as exactly 800 feet, assuming the two angles involved to be identical, and that Test estimated his distance from the shore correctly. I do not think any probable difference in the angles would make a difference of more than 20 or 30 feet in height, while an error of a quarter of a mile in the estimated distance, one way or the other, would make a difference of about 30 feet. The errors due to these two sources, if they exist, may partially, or entirely, neutralize each other; but even if they are both of the same sign, the total error is probably well under 100 feet, and is almost certainly not over this amount. While, therefore, it may be taken as almost beyond question, that the height of the cone was between 700 and 900 feet, it is much more likely that it was between 750 and 850 than outside these limits, and the most probable altitude is about 800.

Lieutenant Whales’ ketch, as produced in the Asiatic Researches (Vol IV) is on a smaller scale than Test’s and shows marks of less careful elaboration. Still, the height calculated from it agrees very fairly with the above, giving the most probable elevation as between 800 feet, the lower figures being the more likely.

Corroborative evidence of a considerable increase in the cone size is afforded by a large protuberance, represented in Test’s sketch on the lower part of the northwestern slope. This was quite obliterated in 1884, owing, doubtless, to its having been buried beneath the ejecta emitted since Test used his brush.

Supposing the true height to have been 800 feet, the cone, which is now 1015, must have just doubled in bulk between the time of Blair’s visit and 1857, since which date we know that there has not been any eruption, a suggestive conclusion regarding the period during which the entire pile may have been heaped up.

Hall, 1795.: The following extract from the log of the ship ‘Worcester,’ commanded by Captain Hall, adds one more to the recorded eruptions towards the close of the last century: -

“Sunday, 20 December 1795. At 10 am commodore made a single for seeing the land. Saw a long island higher at the westward end sloping gently to the westward NW ½ W 14 or 15 leagues off deck. At noon it bore from NW to NW. ½ W take it for Barren or Monday Island. In the centre, smoke arises and has the appearance of a volcano. Its Lat by the bearings is 12° 22’ N. and Long. by my chron. No 1, 93° 54’E Greenwich x x x.

“Monday, 21 xxx. At 6 am, it bore 10 leagues and Narcondam ( both from the deck) NNE ¾ E about 12 leagues. It was astonishing the repeated columns of black smoke which were sent up. There appeared no hill ( as the whole island is nearly a plain surface gently sloping to the eastward as mentioned in yesterday’s log) but the smoke was from the other side of the ridge or on the eastern side.”

Anyone unacquainted with the true topography of the Island, and viewing it from a distance of several leagues might easily suppose it to have a nearly plain surface, or to form a ridge. Captain Hall’s remark that the Island is “higher at the westward end sloping gently to the eastward” agrees with Captain Taylor’s that “the westernmost extremity is the highest, and makes with a peak descending to a low point to the eastward.” But this appearance is evidently a deceptive one, as Captain Hobday’s map shows that the volcano is highest towards the southeast, and we have evidence, in Test’s sketch of the island in 1789, that, as far as the ancient cone is concerned, the outlines then were practically identical with the present ones.

Cason, 1804.: The volcano was again in eruption at the end of January 1804, when HMS “Caroline” passed the island. The log contains the following entry on the 31st – “Several eruptions of fire from the volcano on Barren Island during the night.” This outburst (as pointed out by Dr V Ball) is also mentioned, by one of the officers, in an “account of a voyage to India and China, etc, in HMS “Caroline”. His remarks are given in the following table.

Probable condition of the volcano in the 18th century.: Not one of the observers before Colebrooke (1787) recorded any appearance of smoke rising from the Island or made any remark indicative of their being aware of its volcanic nature, from which it may not unreasonably be assumed that, when they saw the volcano, it was quiescent or at most giving off a little steam. It seems difficult to imagine that while the bearings, etc., of the Island were duly recorded in the log, an eruption if witnessed, should be ignored, and we may, perhaps, further surmise that the volcano was in the same condition when seen by the unknown observers who first applied the names ‘Monday’ and ‘Barren’ Island; at dates we are unacquainted with, but which seem not improbably to lie between 1708, before which time both names appear to have been in use. Had the volcano been in eruption when the observers in question saw it, it does not seem unlikely that they would have given names suggested by the remarkable phenomenon of which they were spectators.

Assuming, however, that the volcano was quiescent at the dates previously given, it would still be unsafe to argue very confidently as to its general condition in the eighteenth century, as, during the intervals of which nothing is known, many eruptions may have occurred for ought we can assert to the contrary. But, at the same time, the fact that on every one of the six dates included in the following records, between 1787 and 1804, the volcano was very active, and mostly in eruption, while on each of the (three or) four dates between 1748 and 1780, it appears to have been quiescent, can hardly be attributed entirely to chance. Hence it can scarcely be doubted that several outbursts during the two decades following 1785 have passed unnoticed, while we shall, perhaps, not greatly err if we regard the preceding four decades as a period of at least comparative, and possibly total, tranquillity. As we have seen, there is also some slight ground for surmising that this tranquillity may have extended back to the early part of the century. Of antecedent ages, we know nothing from direct observation unless the suggestion concerning Linschoten’s map may be taken as one very faint hint.

Tabular abstract.: In conclusion, it may be convenient to add a revised edition of the tabular abstracts given in my memoir on the volcano, incorporating the preceding records, and also the observations that have been made since 1884.