By THAN HTUN (GEOSCIENCE MYANMAR)

EPISODE:50

Mount Popa Region

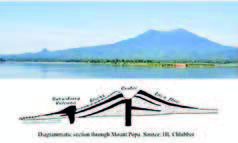

This article describes the igneous activity in the Mount Popa region, as extracted from Chapter XXX of The Geology of Burma, written by HL Chhibber in 1934.

Mount Popa forms the largest and southernmost of the group of Lower Chindwin volcanoes. Most of the lavas resemble the types already described by Chindwin, and the same type names were used in the original description.

The area occupies about 500 square miles and lies between 20° 40’ and 21° 3’N lat. and 95° 6’ and 95° 22’ E long. It is represented on the one-inch Burma Survey map sheets: 84O/4, O/8, P/1, P/2/ P/5, and P/6.

Physical Geography

Mount Popa forms a conspicuous landmark in the heart of the dry belt of central Burma. It is an ideal example of a recently extinct volcano, and it would be difficult to find a volcano more suitable than Mount Popa for textbook illustration. The main mountain originally had a circular crater. Still, the whole of the north-western side was blown away, probably by the final paroxysmal outburst, which suggests that the last eruption must have projected its discharge inclined to the volcano’s sides in that direction. The present mountain is, therefore, shaped like a horseshoe, and it is possible to walk into the crater through the breach in the northern wall. Indeed, cultivation has been carried from the west, the breach is hidden, and the mountain presents the conical silhouette characteristic of an ordinary volcano, with concave slopes steepest near the crater rim. The highest points on the rim are situated on lava flows, marking the points where successive flows, welling out of the crater, escaped over it. The highest points are 4,981, 4,801, and 4,501 feet at sea level, according to the survey maps, and the volcano rises about 3000 feet from its base. The crater wall on the inside is still precipitous in most places- often a sheer cliff with vertical drops up to 1,000 feet.

On the south-western slopes in the extremely precipitous isolated peak known locally as Taunggala (Taungkalat), representing the infilled neck or plug of a subsidiary volcano. The main mass of Mount Popa rests on a level plateau, roughly 1,000 feet above the surrounding plains and about 1,800 feet above sea level. This platform represents the surface level of the land before the building up of the cone and has been preserved by the resistant capping of lava and tuff.

The main mass of Mount Popa should not be confused with the subsidiary ranges of hills to the south and southwest. These hills mark the occurrence of masses of igneous rock of a date earlier than the lavas of the main mountain.

Running southeastwards from Popa is a range of low, wooded hills extending for some 15 miles, as far as the village of Mogan. The higher points are capped by an older lava and the whole seems to have formed originally a continuous flow. On the southwestern side is the Taungni massif of acid tuffs and lavas reaching 1,886 feet above sea level. Quite separated from the Popa hills are the Kyaukpadaung hills, running in an NW-SE direction for about four miles, with two isolated ridges near Kywelu. These hills were found by Hallowes to be composed of acid tuffs and lavas lying to the southwest of Popa and south of the town of Kyaukpadaung. The small isolated vent of Taungnauk, which is an auxiliary of the Kyaukpadaung hills, is seen about two miles northeast of the town of Kyaukpadaung.

General Geology of the Region

It is rather difficult to diagnose the age of two bands of igneous rock unless they are seen in contact. The following table indicates, however, the sequence of the strata in order as far as can be established by field observations.

Formation Age

IX. Stream Alluvium. Recent.

VIII. Volcanic detrital Alluvium. Recent.

VII. The younger Andesites and Basalts with Largely post-Pli associated Tuffs and Conglomerates. ocene.

VI. The interbedded black Tuffs and Ashes. Pliocene.

V. The Taungni and other partially Pliocene.

silicified white Tuffs and Lavas

IV. The Kyaukpadaung silicified Tuffs Pliocene.

and Lavas.

III. The Older Andesites and associated Tuffs. Pliocene.

II. The Irrawaddy Series. Mio-Pliocene

I. The Pegu Series. Oligo-Miocene

Towards the east of Mount Popa, the Pegu Series is exposed, while on the west Irrawaddian sands are seen. The lavas of Mount Popa and other volcanic rocks seem to have been erupted along the Pegu-Irrawaddian junction.

The Older Andesites and the Associated Tuffs

The older andesites lying southwards of lat. 20° 53’N are much older than the rocks of the present Mount Popa, described as “the younger series”. The former exhibit bedding in places and have taken part in the folding movements that characterised the close of the Tertiary period. It is quite probable that the older andesites and the Kyaukpadaung tuffs and lavas are roughly of the same age, though the andesites, as usual, were the first to form, since xenoliths of andesite have been found in the tuffs and rhyolites of Kyaukpadaung and Taungni.

The lower slopes of the hills are often composed of volcanic tuff (conglomeratic in places) overlain by the andesite. Sometimes fragments of Pegu sandstones are enclosed in this clastic rock and the cement is either calcareous or ferruginous.

This lava, as remarked in the section on geotectonics, has participated in the movement which folded the associated Peguan and Irrawaddian rocks. In places, these andesites are characterised by the presence of amygdules filled with pale yellow nail-headed spars which on fracture show radiating structure. These are very common, especially one mile northeast of Okshitkon village, occurring as veins in the andesite and filling the interspaces.

The older andesites as described below comprise the following types:

(1) Pyroxene-andesite.

(2) Augite-hornblende-andesite.

(3) Biotite-pyroxene-andesite.

(4) Pyroxene-andesite with hauyne.

(5) Acid spherulitic andesite.

Gwegon Andesites

Similar, but highly silicified older andesites exist south of the village of Gwegon and west of Konde. There are three isolated outcrops of this rock surrounded by partially silicified white tuffs, one near the Pagoda “1145”, the second marked “1159”, and the third immediately to the south of it. The strike of the rocks coincides with the strike of the main mass of the older andesites and the two may have been contemporaneous in eruption, but it seems likely that this area marks a separate focus of volcanic disturbance and the height of the vents has been lowered by denudation. These rocks consist mainly of pyroxene-biotite-andesites and biotite-andesites, but their striking character is their silicification, a condition brought about by gases and vapours, which also silicified the neighbouring tuffs and so on.

It appears that the Gwegon andesites are intermediate between the basic andesites towards the east and the acidic andesites on the west, and hence afford an admirable illustration of differentiation of magma in the case of extrusive lavas.

The Kyaukpadaung Silicified Tuffs and Lavas

The Kyaukpadaung hills extend roughly in an NW-SE direction and are composed of silicified tuffs with interbedded lava sheets. The latter include rhyolites and andesites. The main hills are continuous for four miles and end about one mile northwest of Sanzu. The other two occurrences, however, in the same line, start about one mile south of where the main hills end and terminate about half a mile south of Kywelu village. About two miles northwest of the twin hills of Kyaukpadaung is the isolated vent of Taungnauk, which has roughly an E-W strike. These pyroclastic rocks are wholly silicified and are very hard, compact, and fine-textured. In places, they show bedding and jointing, as seen near the Pagoda, “1886”. The shade of the rocks is variable, and the specimens are cream-coloured, light pink, yellowish, greyish, reddish, or whitish. Some of the specimens of fine-grained siliceous rocks belonging to this series have all the physical and mineralogical characteristics of chert.

The rhyolite consists of felspar and quartz, sometimes with augite. The felspar is largely altered and pale grey in colour. The growth of quartz seems to be secondary, as its colourless patches exhibit irregular bands of a pale yellow colour similar to those seen in onyx. This is probably due to the diffusion of iron salts, which can also be seen megascopically lining the cavities.

The rhyolite tuffs consist of irregular fragments of quartz and felspar. Both minerals are quite clear and colourless and, in places, traversed by cracks. In some cases, the outline is triangular, and some of the patches of quartz, when observed under crossed Nicols, resolve themselves into microcrystalline aggregates.

The Taungnauk Rhyolite and Tuffs

The isolated Taungnauk hill also, as remarked above, is composed of rhyolites and silicified tuffs. It shows that contemporaneous volcanic eruptions took place at different places, and the two vents near Kywelu afford another striking instance of this fact. Some of the specimens of rhyolites show flow structure and vesicular texture. Disseminated through some of the vesicles are haematite, psilomelane, and carbonates.

Biotite-Andesites: The biotite-andesites described below occur either close to the Kyaukpadaung Hills or interbedded in them. They appear to represent acidic segregations of the magma from which the older andesites described above were formed, but as they are very close to the Kyaukpadaung lavas they are described with them. The four well-marked occurrences of these lavas are on or close to the Kyaukpadaung-Magyigon road. The first one is near the fourth milestone marked on the map. The second is near the fifth milestone, “1145”, near the Pagoda of the village of Wetkyikan. The third is WSW of the village of Thabyebyo at the Pagoda “1007”. The last is interbedded with tuffs about ¾ mile SW of Inbin village. In the second occurrence, easterly dips of 68° are observed. Biotite appears to be almost a constant constituent of these andesites. The following types are found among these rocks: (1) biotite-augite-andesite, (2) biotite-augite-hornblende-andesite, (3) hornblende-andesite, and (4) biotite-andesite.

Age: As regards the age of these silicified tuffs and interbedded sheets of acid lava it appears certain that they are older than the younger lavas of Mount Popa. At the same time, these acidic extrusions were formed subsequently to the older andesites. In places, the two are intermixed, for example, towards the east of Mongan and Okshitkon villages. It may, therefore, be said that the older andesites and the acid lavas of the Kyaukpadaung hills, etc., were formed as a result of the differentiation of the same magma, the latter having been erupted through the former in places, but belonging to the same period of igneous activity. The Kyaukpadaung volcanoes are indeed older than that of Mount Popa, which marks the latest flow that erupted most probably after the deposition of the Irrawaddian. The Kyaukpadaung lavas erupted while the deposition of the Irrawaddian was still in progress, as some of the tuffs were interbedded with Irrawaddian rocks.

The Taungni, Gwegon and Sebauk Tuffs

The main rock is a coarse whitish tuff, partially, or in places, completely silicified. Hard and compact specimens resembling the tuffs of the previous section are associated with these rocks. The rock is so white to resemble a deposit of chalk or calcareous tufa. It is bedded and in places has been thrown into anticlinal folds, which are seen towards the north-east and north of Sebauk Village. In Taungni Hill there is a suggestion of anticlinal structure; the direction of the anticlinal axes is NNW-SSE.

The typical occurrences of the rock are those of the Taungni massif, which appears to be a tuff cone. Its northerly extensions are seen near the villages of Kyaukkon, west of Konde, and east and south of Gwegon. Other similar occurrences are seen towards the north and northeast of Sebauk village extending as far north as the west of Taunggala, “2417”. It will be seen that it accompanies andesite up to the limit of the outcrop; the two are intermixed in places. The siliceous tuffs become agglomerates elsewhere.

(To be continued)

References: Chhibber, HL, 1934: The Geology of Burma,

Mac millan, and Co Limited, St Martin’s Street, London.